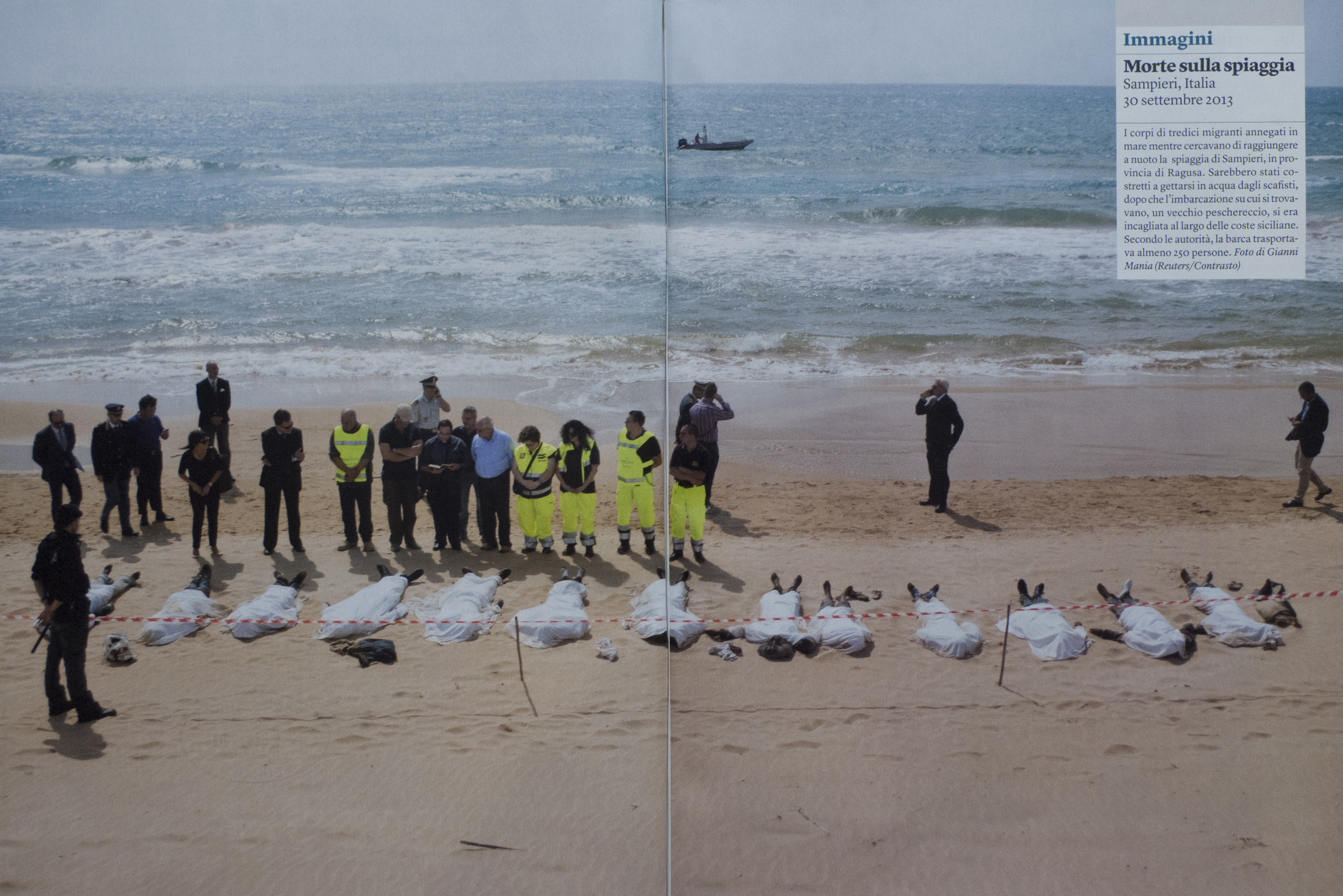

To speak of human mobility is to speak of stories of change, transformation, flight, rescue, encounters and misencounters. Likewise, to approach the information generated on the permanent migratory flows around the planet is to come across statistics that move the soul, trigger alarms and reveal a stark reality: the death of hundreds of migrants in their attempt to find a new life.

A historical example of mortality in high-risk migration processes is the daily situation in the Mediterranean, the continental sea that separates Africa from the Iberian Peninsula and which, at its closest point, the Strait of Gibraltar, only 12 kilometers separate the legitimate aspirations of thousands of migrants from North Africa with the dream destination of another life in Europe.

Despite the global pandemic caused by COVID-19, the massive mobility of migrants across the Mediterranean has not diminished but, on the contrary, has increased significantly, which in turn has intensified the monitoring of multilateral organizations, the action of non-governmental organizations and global condemnation of the blatant violation of international law, as European countries insist on repatriating migrants from countries in armed conflict or, worse still, the lack of assistance policies for migrants on the part of the nations of the Mediterranean basin.

According to data[1] published on the website of the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR), between January and May 2021, the arrival of migrants from North Africa to Europe has increased by 170% compared to the same period last year. This translates into more than 10,400 migrants who have crossed the Mediterranean Sea in highly dangerous conditions.

These numbers also show the very high risk of death by submersion of hundreds of migrants due to the precarious forms of transportation they use, the so-called “pateras”, many of which cannot withstand the harsh sea crossing and the extreme climatic conditions of the region.

This represents a permanent danger that threatens hundreds of African migrants. In fact, April this year was a dismal period for shipwrecks. On 22 April[2], several boats attempting to cross the central Mediterranean simultaneously capsized, resulting in the deaths of 130 Africans from Libya. These deaths brought the death toll to an alarming 500, far higher than the 150 people who lost their lives in the same period in 2020.

Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) dealing with migration in the region, such as SOS Mèditerranèe, responded to a call from the Alarm Phone, a service providing assistance to migrants at risk, as they had been alerted for two days about the mobilization of small boats in risky weather conditions. The SOS Mèditerranèe boat Ocean King was on the scene but it was too late. Its crew described the grim scene as a “sea of corpses”.

In the wake of this high-profile event and the sharp increase in statistics, both UNHCR and the International Organization for Migration (IOM) strongly called on the international community to initiate urgent action to prevent “the growing number of deaths at sea”. The peremptory measures demanded by these multilateral bodies include the immediate reactivation of search and rescue operations in Mediterranean waters, stopping the forced return of migrants to unsafe ports and the creation of a safe and predictable disembarkation mechanism.

The main reason for the call by UN agencies and NGOs that care for migrants in the region is the alarming neglect experienced by displaced people trying to reach European soil, by the authorities in their countries of origin as well as in the destination nations.

The condemnations of what happened on 22 April swept the world and alarmed about this heartbreaking reality: the helplessness to which migrants are subjected, fleeing situations of violence or famine and not receiving the minimum guarantees from the authorities, which is undoubtedly a flagrant violation of international humanitarian law, whose objective is to guarantee the life and well-being of refugees and displaced persons.

“If a passenger plane had crashed, the navies of half of Europe would have come, but they were just migrants, dung from the Mediterranean graveyard, for whom it is not worth running,” Alessandro Porro, president of SOS Méditerranée and a member of the Ocean Viking crew, told the EFE news agency.

IOM regional director Eugenio Ambrosi then wrote on his Twitter account[3]: “These are the human consequences of policies that do not respect international law and the most basic humanitarian imperatives.

For his part, UNHCR’s special envoy for the Central and Western Mediterranean crisis, Vincent Cochetel, who also heads the agency’s office in Europe, strongly condemned the situation and warned that despite the fact that countries in the Mediterranean basin have drones, aircraft, sophisticated telecommunications equipment and rescue boats, “people are still dying on the shores of North Africa”.

“Predictable rescue at sea, disembarkation arrangements and solidarity with the subsequent solutions are more necessary than ever,” Cochetel told EFE[4].

Another of the most vocal condemnations, of course, came from the Supreme Pontiff, Pope Francis, who called the event “a moment of shame[5]” for the world. The head of the Catholic Church did not shy away from pointing out the responsibility of the nations that ignored the call of NGOs to prevent the tragedy of 22 April.

“Let us pray for these brothers and sisters and for so many who continue to die on these dramatic journeys and let us also pray for those who can help but prefer to look the other way,” in a clear reference to the national authorities in the Mediterranean basin who ignored requests for help before the event that claimed the lives of 130 people.

According to UNHCR[6], the bulk of the displaced people attempting to cross the Mediterranean come from Libya, Mali, Eritrea and other North African nations where conflict-related violence persists.

Libya is in a bloody conflict after a NATO-backed revolt overthrew Moammar Gadhafi in 2011 and divided the oil-rich country between an UN-backed government and rival authorities based in the east of the nation. A ceasefire agreement was reached in October 2020[7], but confrontations between foreign fighters and mercenaries unfortunately continue. This situation is causing a large influx of displaced people whose only way out is to migrate across the Mediterranean Sea to Europe.

The same is true in Mali, a West African country facing a critical reality of violence due to the jihadist insurgency that began in 2012. In recent months, Mali has suffered a significant number of terrorist attacks perpetrated by both Al Qaeda and Islamic State groups, which has fueled confrontation between communities and caused the displacement of tens of thousands of refugees.

However, it is the issue of Libya that remains intensely in the media not only because of its permanent conflict and the continuous contingent of displaced people that this provokes, but also because of its geographical position in the central Mediterranean and its proximity to Greece and Italy, which intensifies the flow of migrants in the area and, therefore, the risk of death of hundreds of migrants.

The Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC), an NGO working in Libya to assist war-displaced people, warned Europa Press[8] news agency that by May 2021 the death toll in Mediterranean waters could already reach 600 and that this tragedy could be avoided “if Europe would allow rescue missions to take migrants to safety instead of avoiding taking responsibility”.

These statistics are confirmed by the IOM on its official page[9] dedicated to the Mediterranean death crisis.

In short, African migrants suffer a multifaceted threat to their lives and well-being as they attempt to cross the Mediterranean in search of a new life: the violence of the armed conflict in their countries (to which European authorities insist on returning them), the precarious conditions of maritime transport (“pateras” and unstable weather) and the abandonment of the authorities in the Mediterranean basin (especially in Europe) who do not offer the minimum guarantees for the well-being and life of displaced persons, thus violating international humanitarian law.

[1] Disponible en: https://www.acnur.org/noticias/briefing/2021/5/ 6091c5e94/acnur-alerta-sobre-el-creciente-numero-de-muertes-de-personas-refugiadas.htm

[2] Disponible en: https://www.acnur.org/noticias/press/2021/4/608318e54/ acnur-y-oim-el-creciente-numero-de-muertes-en-el-mediterraneo-central-exige.html

[3] Disponible en: https://twitter.com/AmbrosiEugenio/status/m13853 09509682405376?s=20

[4]Disponible en: https://www.efe.com/efe/america/sociedad/ongs-un-centenar-de-victimas-naufragio-fueron-abandonadas-a-su-suerte/2000 0013-4519565

[5] Disponible en: https://www.telesurtv.net/news/vaticano-papa-francisco-naufragio-migrantes-verguenza-20210425-0009.html

[6] Disponible en: https://www.acnur.org/noticias/briefing/2021/5/ 6091c5e94/acnur-alerta-sobre-el-creciente-numero-de-muertes-de-personas-refugiadas.html

[7] Disponible en: https://apnews.com/article/noticias-aa2237dd0ceed157701e728ce7366334

[8] Disponible en: https://www.europapress.es/internacional/noticia-mas-600-migrantes-muerto-aguas-mediterraneo-principios-2021-20210503134842.html

[9] Disponible en: https://missingmigrants.iom.int/region/mediterranean