Newton’s Third Law is categorical: For every action there will be a reaction with the same and proportionally opposite force. And it happens in all human phenomena, including politics. For every action an equal reaction is expected. Today, the problem is that there are hegemonic instances that, unable to execute actions that favor their particular interests, because they are unpopular, anti-democratic or contrary to the law, consequently design “actions” that will justify eventual “reactions”, which will then be socially accepted as necessary, expected and urgent.

The same thing is happening in the world of geopolitics and international relations. In recent years, States dominated by neoliberal and nationalist governments have sought to respond forcefully to situations that were precisely discursively constructed, both by themselves and by their strategic allies, in the media and other spaces of political interaction, such as international forums and multilateral organizations. One of these “created” situations, whose hidden purpose is to justify radical policies and measures, is the consideration of mass migration as a threat to the national security of the receiving countries. And the solution proposed by the States is the socalled securitization of migration.

The social representation of migrants as a threat to national security is a direct result of the criminalization process to which they are subjected. It is a discursive construction promoted by those States that seek to restrict the entry of migrants from other countries and justify the enormous amount of financial resources allocated annually to design and implement policies that, in the eyes of national and world public opinion, are necessary to protect those nations from the danger posed by migration.

In the book Pensar las migraciones contemporáneas (To think the contemporary migrations), coordinated by researchers Cecilia Jiménez Zunino and Verónica Trpin (Teseo, 2021), in the article Securitization of migrations, signed by Andrés Pereira and Eduardo Domeche, it establishes that the term securitization of migrations is a category produced “within the framework of the process of political production of migration as a security issue at the international level and in a context of tightening of migration and border controls in the North Atlantic area, both in the United States and Canada and in the European Union”.

The authors warn that, in Latin America, the application of the securitization of migration varies according to the nature of migration policies and the forms that inequality and violence against migrants have taken in each country or region. “In general terms, in Mexico and Central America, it has been used to account for the externalization of U.S. border control policies and the experiences of disappearance, kidnapping and death of migrants on their way north.

Pereira and Domenech emphasize that, with some exceptions, the use of the category is associated with changes in national migration policies, especially since the so-called “shift to the right” in the region, with which a generic use of the term prevails to denote migration regulation schemes associated with “national security” and linked to processes and practices of criminalization of migration.

This underscores the imposed logic of action-reaction to justify ever harsher border security and surveillance policies. In other words, migrants are criminalized (in some cases also the solidarity groups that assist them), thus becoming a threat to national security and, consequently, justifying the measures.

These measures range from the promotion of legislation that serves as a legal framework for the design and execution of public policies on migration issues, to the allocation of financial resources to make possible the expenses involved in the creation of public and private institutions, the acquisition of surveillance equipment, the hiring of personnel and the execution of practices or operations such as the detection, capture and deportation of migrants. The latter are the most criticized because, in most of the cases recorded, they limit or violate the human rights of migrants.

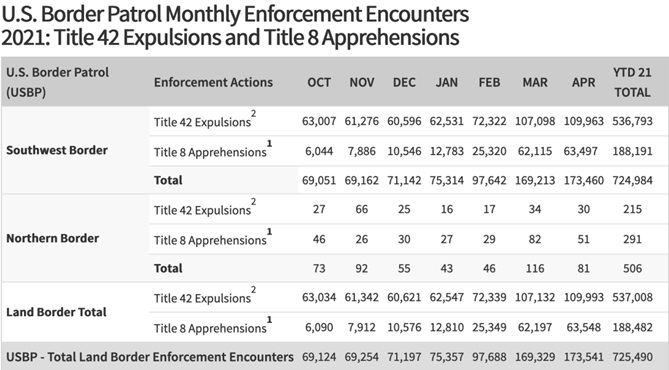

As has been pointed out, the most notorious case and the one that serves as the most tangible example of what is understood by the securitization of migration is what happens at the southern border of the United States, the point of entry of the intense and permanent migratory flows that, from all parts of the world, try to enter the North American nation.

An emblematic date that marked a milestone is September 11, 2001. Researcher Javier Treviño Rangel, in his academic article “What are we talking about when we talk about the securitization of international migration in Mexico? A Critique, indicates that despite the fact that such practice already existed, 9/11 (as Americans identify the event) justified before public opinion the authorities’ power “to detain migrants who cannot accredit their legal stay in the country or to promote centers where migrants are deprived of their freedom.”

For the authors, this event also initiated, like no other, the belief that undocumented international migration is a threat to national security and served to make not only the US but also other states -Canada, for example- radically harden their policies towards international migration.

In fact, as a result of 9/11, institutions were created in the U.S. that today are the main executors of the harshest immigration policies on the southern border and where the greatest amount of financial resources are concentrated.

An exponential budget According to a report by the EFE news agency, in 2003 the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) was created, which currently controls and administers a budget of US$381 billion, through border surveillance and immigration management agencies.

A report released in 2020 by the American Immigration Council indicates that immigration enforcement is carried out by Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and the “dreaded” Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), both agencies under the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and whose primary function is the detention and deportation of undocumented immigrants.

According to the report reported by EFE, ICE and CBP currently employ more than 84,000 officers, of which more than 50,000 (55.5%) perform specific law enforcement duties.

The budgets of both agencies have experienced exponential growth since their creation. For example, since 1993, according to the report, “when the current border enforcement strategy was initiated along the U.S.-Mexico border, the annual budget of the Border Patrol, which is now part of CBP, increased more than 10-fold, from $363 million to nearly $4.9 billion”.

Also, planned spending for ICE between 2003 and 2020 increased from $3.3 billion annually to $8.4 billion. According to the American Immigration Council, the funds were earmarked primarily to “increase the agency’s capacity to confine detained immigrants at sites across the country.

The importance of the securitization of migration in the U.S. is reflected not only in the funds allocated to the erection of fences and fences, surveillance technology, unmanned aerial vehicles (drones) and the construction of buildings for detainees, but also in the increase of Border Patrol agents, which went from 4,139 to 19,648 in the 2019 fiscal period, “still below the authorization of Congress for the hiring of 23,645 agents,” notes EFE.

Policy continuity?

Security and investment It is possible that with the departure of Republican Donald Trump from the U.S. presidency it was naively believed that migration policies would be relaxed, but this was not the case. Although on his first day in the White House, Democrat Joe Biden revoked the executive order issued by his predecessor on January 25, 2017, which, among other issues, criminalized the undocumented stay of migrants as a threat to public and national security, he nevertheless reiterated that his administration’s policy would focus on protecting national and border security.

According to an analysis made by the Latin American Strategic Center for Geopolitics (Celag), entitled The Biden Doctrine in Central America, migration policies are a clear example of the permanent U.S. policy of securitization of migration to justify not only national security policies but also, and above all, economic investment.

“It is assumed that Biden will go for a comprehensive immigration policy, but that it will not necessarily be less securitized. The Comprehensive Strategy for Central America has a projected budget of four billion dollars, obtained through Security funds and private sector investment, as well as greater participation of the World Bank and the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) in the development of infrastructure and FDI in the region,” reads the Celag analysis.

It is important to clarify that FDI is the acronym for Foreign Direct Investment, that is, the economic intervention made by the U.S. in other countries and in which it holds not only the power to choose the companies (almost always associated with the government of the day) but also to maintain operational and financial control of such investments. In other words, the securitization of migration has as its background an economic interest, which is what Democrats and Republicans always agree on.

For such reason, Celag warns in its analysis how on February 2, 2020, Biden ratified, through three executive orders: 1) the migration measures linked to family reunification, 2) the creation of a comprehensive regional framework to address the causes and improve the management of migration flows from North and Central America, and 3) the possibility of providing safe and orderly processing of asylum seekers of those migrating across the US southern border, but that same day they clarified that these actions did not mean “that the borders are open” but were “one more step in the strategy that aims to stop forced migration through cooperation in the fight against corruption and impunity.” We see here how migration continues to be associated with crime, in this case institutional or governmental.

Throughout the electoral campaign, Biden presented himself as opposed to Trump’s management of migration issues. However, it was Obama who proposed the so-called Alliance for the Prosperity of the Northern Triangle of Central America as a solution to the humanitarian crisis resulting from the increase in migration and Biden as its main articulator, meeting intensively with leaders and officials of the Northern Triangle countries to draft and implement the guidelines of the Alliance, policies that were announced as part of a regional security plan but that also meant a significant financial investment in countries of the Mesoamerican region.

In other words, the securitization of migration in the Central American region will continue to be presented as an urgent and necessary reaction to the threat to national security posed by the massive exodus of migrants, but which in essence justifies a significant economic investment, both abroad and in U.S. territory, which translates into benefits for those in power in the nation of the American dream.

For this reason, the discourse of criminalization of migrants will surely be maintained in order to continue legitimizing a reaction “with the same force and proportionally opposed” in terms of security, albeit with very high financial and economic implications for the U.S. government of the day.