Draws attention the invisibility of migratory phenomena that, due to their dimensions and impact, it should occupy a prominent place not only in public opinion but also in the agendas of States and international organizations.

A clear example of this is the dramatic situation in the so-called “Forgotten Border” between Panama and Colombia, a winding line 266 kilometers long, located in a wild and inhospitable area, which leaves at the mercy of the dangers of the jungle, organized crime and drug cartels to thousands of migrants attempting to cross this dangerous sector on their way to the United States.

It is the so-called Darien Gap, an area almost inaccessible due to its extremely dense jungle that interrupts the extensive Pan-American Highway and separates Central America from the southern region of the American continent. Because of its dangers, mysteries and stories, it is considered an emblematic place on the route of migrants from all over the world, mostly Haitians, Africans and Cubans, in their desperate search to reach the “American dream”.

It is known as “El Tapón” because it is a jungle block of 5,750 square kilometers, located between the Panamanian province that gives it its name and the Department of Chocó in northern Colombia, which can only be crossed by air or water and serves as a natural barrier between the two nations. In addition, the area is known worldwide as “the most dangerous jungle in the world”.

The area is so rugged that it could only be traveled in its entirety by road, between 1959 and 1960, in an expedition formed by the British Richard Bevir and the Australian Terrence Whitfield, aboard a rustic European-made van. However, the vehicle could only make part of the journey, as they had to use improvised bridges and boat transfers to complete the trip, which took almost five months and ended on May 13,1960. Bevir and Whitfield achieved what was impossible for the first Spanish explorers who arrived in the area in 1510, precisely because of the dense vegetation and dangerous fauna, threats that even today loom over the hundreds of migrants who cross El Tapón every day to continue on to the United States.

In recent years, the Darien Gap has begun to be talked about a little more, not only because of its multiple dangers, ranging, as has been noted, from ferocious jungle animals, highly violent plagues, the impassable nature of its topography, to its risks as an area of drug trafficking and organized crime, but also because of the high rates of human mobility in the midst of the global pandemic and the number of children who undertake the dangerous journey, often unaccompanied, between winding waters, swampy areas and jungle forest, in a journey that today can be done in a period of seven to ten days. It may not seem long, but according to testimonies it is a traumatic experience.

In fact, in the latest report on Extra-regional Migration in South America and Mesoamerica: Profiles, Experiences and Needs[1], published by the International Organization for Migration (IOM) in April 2020, the organization recommends improving psychosocial care after crossing the jungle border, since “the migrant population, after crossing the Darien Gap, presented conditions of vulnerability, deterioration and psychological affectation, in addition to the loss of their economic resources for the trip”.

The same report states that this rugged point between the border of Colombia and Panama was identified by migrants as the most risky place for their journey due to geographical and climatic conditions, as well as the presence of organized crime networks. “Likewise, there is a worrying increase in the number of minors under 18 years of age at this crossing point,” the text reads.

According to data[2] from the United Nations Children’s Fund (Unicef), in 2019, nearly 24,000 migrants of more than 50 nationalities, from countries as far away as India, Somalia, Cameroon, Congo and Bangladesh, crossed the Darien Gap on foot. Of these, 16% were children, mostly under the age of six.

For Unicef, the most worrying factor was to identify that the number of children migrating through this route increased sevenfold in one year, from 522 children in 2018 to 3,956 in 2019. There were also 411 pregnant women and 65 unaccompanied children reported. From January to March 2020, Panama’s National Migration Service recorded the entry of 4,465 people, of which 1,107 were under 18 years of age.

“The number of children of Chilean (411) and Brazilian (192) nationalities is significant. The closing of borders in Central America as a result of COVID-19 left 2,522 extra-continental persons in migratory transit through Panama confined in the Migratory Reception Stations (ERM), of which 27% are children and adolescents, including four unaccompanied adolescents”, states a report[3] by the Unicef Office in Panama, published in April 2020.

But the plight of the migrants and the minors accompanying them does not end when they cross the jungle and circumvent its dangers. It is no coincidence that Unicef uses the term “confinement” to identify the state of the more than 2,500 migrants who occupy the facilities of the Panamanian ERM. In these facilities of the National Border Service (Senafront), specifically in Puerto Peñita, the migrants are held while migration authorities coordinate with their Costa Rican counterparts the resumption of their transit through both countries. At that checkpoint, they participate in interviews, fingerprinting and other biometric records, which takes up to a week, although some people report that they have been waiting for a month and without the possibility of leaving in sight, due to the large number of requests and the fact that Panamanian and Costa Rican authorities agreed on a limited number of daily authorizations, according to reports received by the IOM.

The task is also made difficult by language barriers. According to official data from Panama’s National Migration Service, 57% of the migrant population in transit is of Haitian origin, many of them fleeing the economic and political situation in their country. The rest (43%) come from Africa (22%) and Asia (17%), with the remaining 4% coming from South America, which makes it difficult to attend to those in transit.

The IOM reports in the aforementioned report[4] that “the lack of information on the origin of the migrants and the language barrier were obstacles to personalized assistance to the groups by the authorities. In addition, they pointed out that the centers were conglomerating people from very different cultural and educational backgrounds, and that in some cases this generated conflicts among migrants, since many of them preferred to be grouped with people of the same nationality.

The origins are so varied that according to a report[5] in the Spanish newspaper El País, “in Bajo Chiquito, the Emberá indigenous community that is the first contact with something resembling civilization after days of trekking through the jungle, the Senafront post has a blackboard where he points out the different nationalities that appear: Congo, Bangladesh, India, Cameroon, Nepal, Angola, Pakistan, Burkina Faso, Sri Lanka, Eritrea, Guinea, Ghana, Sierra Leone…”. These citizens, as well as Haitians, use countries such as Ecuador to enter the American continent to then embark on their journey to the United States or Canada.

Crime and death in the jungle

In addition to the dangers of the jungle and the intense transit of migrants from all over the world in the area, as mentioned above, there is also the risk posed by organized crime operating in the Darien Gap region.

According to the IOM, in addition to reported vulnerability, due to language difficulties, access to information and medical services, migrants have lost money, identity and travel documents due to theft during their journey through the jungle. “The loss of these documents implied difficulties in accessing financial services, as it is usually a requirement to receive money. According to the people interviewed, this forced them to take various measures to access the money sent by their relatives or friends, such as requesting that private individuals carry out the transaction, and this increased their risk of suffering fraud,” the IOM report states.

Added to this are the dangers of criminal violence by criminals involved in human trafficking, such as sexual abuse against migrant women and the disappearance of migrants, statistics that are difficult to calculate since there are data on the arrival of foreigners in Panama, but not on the number who enter the jungle to cross the border.

Likewise, crime in the Darien region has increased in the last decade at the hands of drug cartels, which began to use this rugged route due to intensified surveillance in other previously used corridors and as a remnant of Colombian mafias that have concentrated on other forms of transportation.

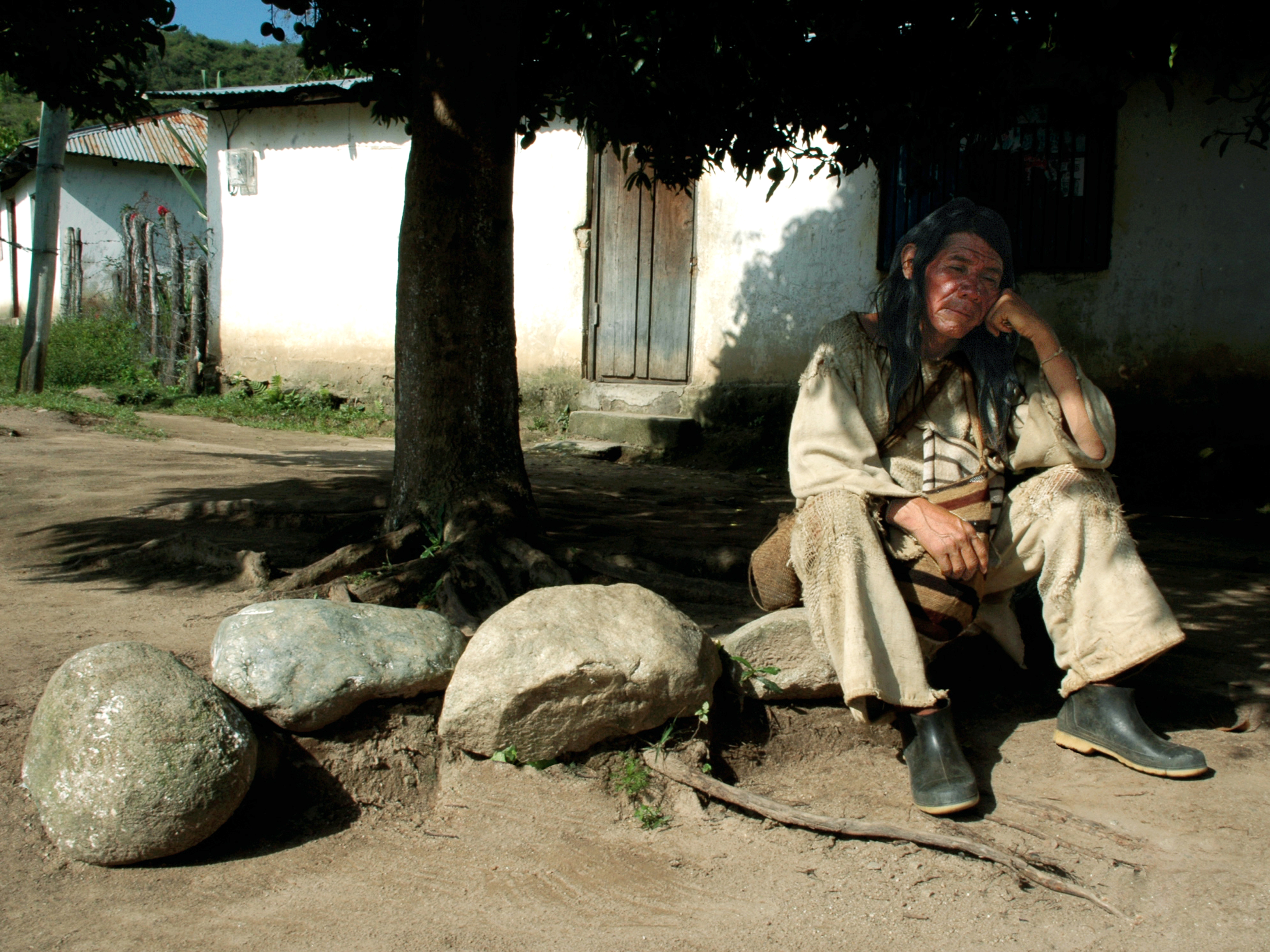

“The drug traffickers come here. They offer considerable sums of money to our young people to work,” Trino Quintana, head of the Emberá ethnic group, which inhabits an area located in the Yaviza region and the northern part of the Darién Gap, a semi-autonomous indigenous territory, told the BBC[6] in 2014.

Abandonment by the authorities and solidarity

With the headline “Darien: border crossing that continues to cause the death of migrants”, in June 2021, the newspaper La Estrella de Panama reported the latest deaths of migrants registered between April and May of this year, due to the dangerous conditions of the jungle.

On May 30, 2021, three victims were found by Senafront on the banks of the Marraganti River, in the Emberá Wounaan comarca (Panama). In April, another four bodies were found in the Turquesa River, between the Wargandi and Wounann comarcas, in the jungle region of Darien. All the victims, according to the authorities, had perished by immersion. However, it is not possible to calculate, as mentioned, the disappearances due to criminal violence and diseases caused by the precarious climate of the region.

According to the IOM, 20% of those interviewed on the Panamanian side reported having suffered hunger and thirst during the crossing and 77% indicated that their children suffered from some health condition during the journey, mainly gastrointestinal infections, skin rashes and fever.

In short, the multiple failures in the attention given to extraterritorial migrants on the Colombian-Panamanian border, together with the extremely high risks of the Darien jungle and the threats of organized crime, make this group of migrants a highly vulnerable sector, which continues to experience a dangerous media silence or, at least, a timid news treatment, in favor of other issues that are beneficial to impose more radical migration policies or for the frantic search for funding in other areas of migration management such as securitization and border surveillance.

“And no one is helping them. They are overcharged, mistreated; they sleep in the streets and go hand in hand with coyotes linked to armed groups. However, here there is no sign of humanitarian organizations or the State,” concludes a report by[7] BBC Mundo on the migrants trying to cross the “most dangerous jungle in the world”: the Darien Gap.