Introduction

In recent months, Frontex has come under increasing criticism due to its responsibilities and links to human rights violations against migrants heading towards the European Union. However, it is possible that the seriousness of the matter is not perceived by the public, despite the denunciations of civil society organizations and even UN agencies.

Unfortunately, it is possible that Frontex’s actions, far from being a deviation from its mandate, clearly respond to European Union policy, especially in the context of the rise of extreme right-wing movements with access to spaces of power, as well as with the consolidation of an Islamophobic vision derived from the 2015 refugee crisis and the terrorist attacks perpetrated on European soil in recent years.

In the following, a brief reference will be made to Frontex, as well as to the Schengen Treaty on which it is based. We will then go on to briefly review the performance of Frontex over the last few months, in line with the complaints that have been made public in the press. Finally, we will give an account of the reaction of the European institutions to the criticisms received.

¿What is Frontex?

It is the European Border and Coast Guard Agency, which was created in 2004 and reformed only in 2016, in order to extend its functions to surveillance and rescue tasks with its own personnel. It is made up of the various security bodies of the Schengen Treaty member nations with border control responsibilities, in addition to its own personnel and equipment. Among its tasks is the collection and sending of information to the security forces of member countries, analysis of vulnerabilities of the external borders with special emphasis on the risks of terrorism and cross-border crime, among others [1].

In turn, the Schengen Treaty is the legal instrument that allows many European countries to share border control procedures. Although the Schengen Treaty dates back to 1985, it was not until March 1993 that it came into force for the first group of countries, including Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Germany, France, Italy and Spain [1].

The text of this treaty establishes the concepts of internal and external borders. Thus, internal borders are those shared by two-member countries of the treaty, as well as airports and ports, provided that the points of origin and destination of travel are within the territories of the member countries. External borders are defined by corollary, so that we are talking about the boundaries between member countries and non-member countries [1].

This imposes a substantive change in the traditional conception of borders, which has enormous consequences from the administrative point of view. From then on, the member states of the Schengen Treaty will reorganize the control and surveillance of their borders, as well as everything related to the granting of visas, with a single codification, the creation of a list of inadmissible persons, among others [1].

Likewise, the member countries ceased to carry out surveillance and control tasks on their common borders, while concentrating personnel and resources on greater control of their external borders. Thus, instead of devoting efforts to controlling the border between France and Spain, or between Germany and the Netherlands, the focus was on the Mediterranean basin, the Balkans or Eastern Europe.

In principle, neither the Schengen Treaty nor Frontex should pose any human rights problems, except for the fact that the control and surveillance of external borders have been based exclusively on a conception centered on security, on the prevention of terrorism and transnational crime, as well as on a markedly racist and aporophobic vision, while considerations of people’s rights to seek asylum or refuge, and even to be treated in accordance with the law, have been relegated to the background.

Over the last five years, and as a consequence of the reform, Frontex has evolved from a coordination mechanism between police forces to a multinational security force in its own right, with its own identity, which has not gone unnoticed by those committed to the protection of human rights [2].

A report by the Pro Causa Foundation reported in June that Frontex went from having 50 employees and 6 million euros in budget in 2005 to becoming the decentralized EU agency with the most staff and the largest budget in the European Union, with a total of 1,200 employees and the management of 460 million euros. The Foundation complains that Frontex “seems to have taken on a life of its own, acting without transparency or control, taking over executive functions from member states and turning the securitization of migration into a self-fulfilling prophecy,” and adds that the agency has embarked on recruiting, deploying and equipping (including weapons) 10,000 border guards [3].

¿What is the problem with Frontex?

Frontex is the enforcement arm of EU migration policy, and is responsible for coordinating, promoting or executing clearly illegal actions of force against irregular migrants trying to enter European territory.

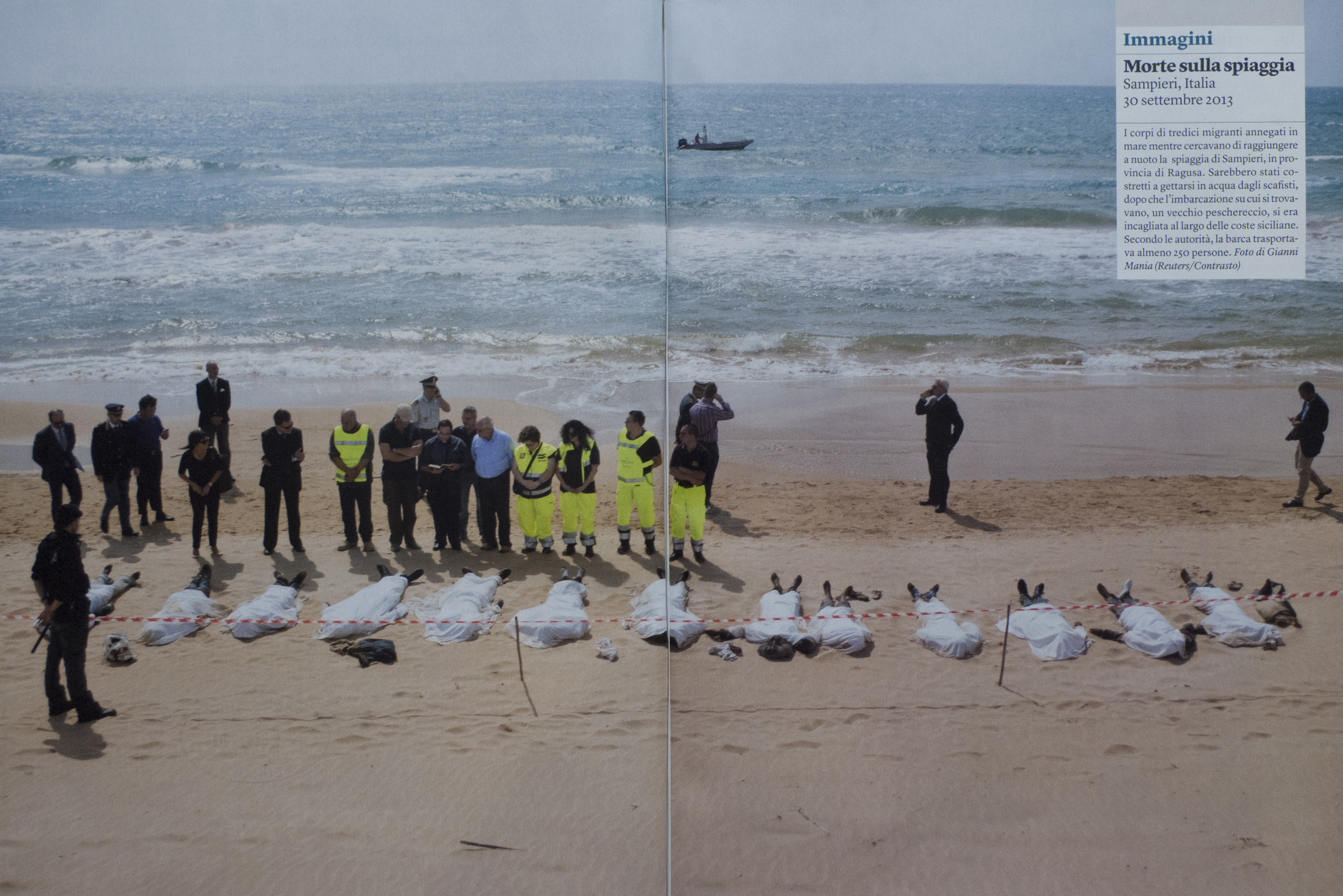

According to the Abolition of Frontex network, an estimated 45,000 people have died between 1993 and 2021 due, directly or indirectly, to the actions of this agency, as well as associated law enforcement agencies in each member country [4], which can be broken down as follows:

• People drowned in the Mediterranean Sea or in the Aegean due to a combination of factors such as the use of unsuitable vessels, the refusal to provide support or coordinate rescue actions at sea, the obstacles encountered by nongovernmental rescue organizations and hot returns. The estimates do not consider the so-called invisibles sinking’s, which are not reported.

• The suicides that many people commit due to the desperate situations in which they find themselves as a result of refoulement in highly vulnerable conditions and internment in detention centers.

• People killed as a result of shooting at the external borders. This estimate does not include those people who could have been killed by shots fired by the Libyan coast guard, a country that has agreements for migration control with the European Union, in exchange for money [5] [6]. In 2020, due to the situation generated by the pandemic, the number of asylum applications in EU countries fell to 2013 levels, before the refugee crisis resulting from the war in Syria. However, the flow of migrants through the Balkans increased, due to the large number of people being held beyond the external borders. The enormous difficulties for the transit of these migrants, as well as the appalling conditions in which they survive, are nothing but the consequences of an iron control device installed by countries such as Hungary and Croatia on their respective borders with Serbia, among other cases, all with the support of Frontex [7].

The non-governmental organization Save the Children recently denounced that Croatian police are involved in the use of violence against migrant minors, as well as in the murder of at least one of them, in transit to the European Union, which is particularly serious [8].

Even more serious are reports of forcible returns by Greek border authorities at Evros, the land border between Turkey and Greece. According to an Amnesty International report, hundreds of people have been forcibly returned between June and December 2020. It is known that there is a strong Frontex presence in this area which supports the Greek authorities in some way [9].

In addition, the Greek authorities are also accused by the Turkish government of preventing boats with migrants from reaching their shores, leaving them adrift and in danger of sinking. On occasion, the Greek coast guard has disabled boats to prevent their movement, leaving people to their fate [10].

These unlawful actions have attracted the attention of multilateral organizations. Recently, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Filippo Grandi, pointed out that certain actions were undermining Europe’s reputation, referring to the illegal and indiscriminate refoulement of migrants at the Union’s external borders [11].

¿What is the EU doing in relation to Frontex?

However, in view of this situation, it is worth questioning the EU’s plans in relation to migration. Far from taking note of reports of human rights violations against migrants, and taking measures to ensure their protection, there have been certain restrictions on the movement of people at internal borders, given the increase in the number of asylum seekers since 2015, which compromises the economic functioning of the Union. Due to this situation, there are plans to strengthen the external borders through Frontex with a state-of-the-art digital entry and exit system, as well as more cooperation between police and national security agencies, all aimed at increasing confidence in each member country that the others are ensuring common security in the face of threats such as terrorism and transnational crime [12].

Technology seems to be the most relevant change that will be experienced in relation to external borders in the coming years. Currently, at the border between Greece and Turkey, as well as in countries such as Latvia and Hungary, a security network is being tested with long-range cameras and night vision, as well as different sensors whose information will be analyzed through artificial intelligence to detect movement of people on land, or boats at sea. Likewise, lie detectors with artificial intelligence, automated border interview systems, integration of satellite images with images taken by drones on land, in the air and under the sea, as well as biometric readers that register the pattern of the veins in people’s hands for their correct identification have been tested. This is a set of projects for which the EU has invested more than 3 billion euros in research into security technologies that will make it increasingly difficult for asylum seekers to reach safety [13].

On the positive news side for migrants. The European Commission launched a program called “Partnerships for Talent”, through which it seeks to address the shortage of skilled labor to boost innovation [13]. Unfortunately, those we have been talking about are precisely the poor and low-skilled migrants, victims of human rights violations by Frontex, and who are likely to continue to receive the same treatment as they have to date.

Endnote

The future of Frontex’s performance does not give cause for optimism. There is no indication that the EU is reviewing in depth the allegations against Frontex in relation to the violation of human rights of migrants. On the contrary, a reinforcement of the agency’s capacities to effectively prevent irregular migration is announced, as well as the practical impossibility to apply for asylum in the EU.

Greater technological sophistication for the detection of irregular migrants will not prevent them from continuing to try to reach European territory, but the ways of gaining access will certainly be much costlier, and above all much more dangerous for the personal integrity and lives of people, including women and children under 18 years of age.

So, unfortunately, we will continue to see the consequences of a policy focused on security within borders, as well as the dehumanization of migrants and refugees from Africa and Asia.

Due to this situation, at Argos we advocate for a profound change in the European Union’s migration policy, and we join the campaign promoted by the Abolish Frontex Network, as well as many other organizations in solidarity with migrants and refugees around the world.

References

[2] https://apnews.com/article/noticias-b180ecee22689d0 6b7630014694f2b78

[3] https://www.eldia.es/canarias/2021/06/17/canarias-siguelampedusa-limbo-migrantes-53671814.html

[4] https://www.dailysabah.com/politics/eu-affairs/ngoslaunch-campaign-for-abolition-of-eu-

[6] https://apnews.com/article/8ea6dbded43d36efe61ed9 ececbcb84b